April 2015

We have had an astounding outpouring of support and interest for the workshop and we have assembled a stellar cast, many with international careers. I am so excited to be working with such an enthusiastic and committed team. Working around the clock to get materials to singers and instrumentalists. In the process of orchestrating for our little “band” I, of course, have to make more revisions. We’ve just been selected to be featured in Opera America’s New Works Forum in January 2016 which will coincide with the next workshop.

I have been rehearsing with Kendra Broom, a fabulous mezzo who looks 15 and so totally gets Mariam. Next week I rehearse with all of the women, there is a festive market scene which actually has some of the most difficult music in the whole opera (thus far). I will post some pictures….

December 2014

It has been a wonderful six months. Over 45 min. of music have now been composed and I am getting ready to distribute scores to our singers and performers for our workshop on June 1, 2015. It will include Act I, scenes 1, 2, and 3, plus excerpts (love music) from scene 5. Even more thrilling was making the recent recording and finally hearing some of the music with real singers. Vira Slywotsky (Nana) and Cynthia Cook (Mariam) are both incredible artists and I am excited for others to hear the great work they have done with this music.

We have brought on Sara Jobin, the first woman conductor of the San Francisco Opera, as conductor of the workshops, and Leslie Swackhamer, as director of the workshops. I met both of them in San Francisco at the Opera America Conference, where I was a guest, in June. Leslie worked with Jun Kuneko to develop a Butterfly that has had dozens of productions worldwide. I saw it at San Francisco and was wowed.

My study of Indian music continues. I’m using Lalit for Rasheed and Shuddah Sarag in the Market scene, which is very merry. I even used a “farmaisha” — a long rhythmic composition — that I had been practicing on tabla — in a climactic instrumental part of the market scene music. But everyone says the music does not sound “Hindustani.” It just sounds like my music. [back to top]

May 2014

I have received one of the eight Opera America Grants for Female Composers funded by the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation, which means that sometime next year we will have a workshop with several singers, and an ensemble of at least 5 instruments. I have been composing, having worked on the Prologue, Act I, scenes i, ii, and iii. Each are in various states of completion. Ragas incorporated thus far are Bhairav, Bairagi, Bilaskhani Todi, Miya ki Todi, and Lalit. I’m finding that the ragas give a particular color to my already tonal language and influence thematic material. I’m not strict or literal — but the underpinnings of the raga are often present. We had a reading of the libretto with 8 talented actors a couple of weeks ago in New York City and Matt Gray, who runs AOP’s Libretto Reading Program said it was one of the best libretti he’d seen in a long time. Kudos to Stephen. Stephen hears everything I compose and offers suggestions. In our fast paced action filled opera, we need to calculate carefully where the rest periods (i.e. arias) come. I will be going to the Opera America Conference in June in San Francisco to learn more about the industry. We are eager to connect with our production partners.Back to top

March 2014

I am back in the U.S. and have begun composing. It feels wonderful defining my language as I begin to work with ways to bring my Indian studies to my own voice. I continue to study (thank you Skype) with my guru (thank you Kedar) and singing is still part of my daily routine. In fact, I’m really enjoying singing the lines I’m writing for my opera singers. I figure if I can sing them, they can sing them. Stephen and I have honed our libretto but I still make lots of changes when I’m actually composing. We recently made some significant cuts and moved from a Three Act to a Two Act opera.

September 2013

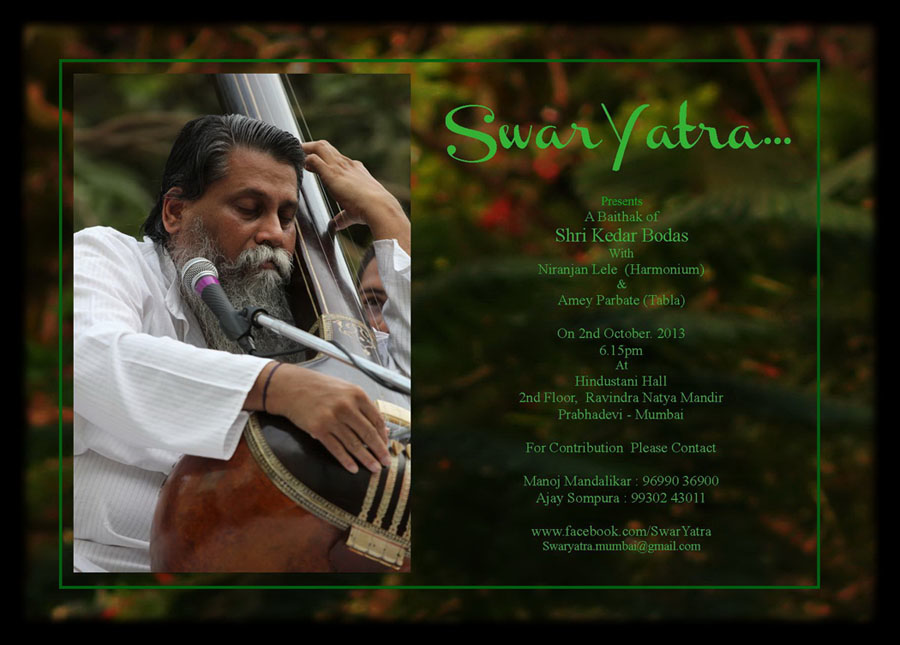

We are now 3 months into our stay in Pune and my study of Hindustani music, in preparation for composing A Thousand Splendid Suns, is proceeding in leaps and bounds. In January of 2013 I began a long-distance study of Hindustani music under the mentorship of Deepak Raja, author of Hindustani Music, A Tradition in Transition, and since June of 2013 I have been living in Pune India, studying singing North Indian classical music (khayal and a little dhrupad) with master singers, Pandit Narayanrao Bodas and Sri Kedar Narayan Bodas. They have opened an entirely new world of sound to me — and opened their home and their hearts to me as well. It is thrilling to be a student again and I will return home with a wealth of ideas and “source” material for my opera. I am also studying tabla (Indian classical drums) and this work is also presenting me with fresh rhythmic possibilities. My study of North Indian music will “color” my Western compositional voice — North Indian music being at the heart of Afghan music. The Bodas’ are both extraordinary musicians and it is a privilege to be able to learn from them in the traditional “Indian” way. I am not only learning Indian music — I am also learning much about the deep traditions of Indian music and how it is taught and conveyed. Yes, I am being transformed — and … it will all go into the opera. We definitely have a big powerful opera here.

Meanwhile, Stephen Kitsakos and I have made great progress. Before I left NY we had finished the adaptation. He has now completed the first act of the libretto. I am thinking hard about how to incorporate the amazing sounds I am experiencing and how to create an authentic Afghan color (Afghan music is based on North Indian music) in my Western voice. Things like — making the orchestra sound like a tanpura; orchestrating the colors of the tabla, each stroke having its unique identity in a maze of rhythmic patterns; how to create the slips and slides and bends that are so particular to Hindustani music without asking too much of our Western musicians. I have already decided that I will include tabla and bansuri (bamboo Indian flute) in my otherwise Western orchestra. One of Kedar’s students is a professional bansuri player and I have the opportunity to listen regularly to its intricacies. It makes a gorgeous sound and is so flexible. It will add an exotic color. I even visited THE world’s leading bansuri maker with Kedar and Amar, his student, in the home of Pune’s flute master, Keshav Ginde, where Pune’s finest flutists gathered to sample the wares. John and I are the two “goras” (gringos) in the photo. I am very excited to begin composing but am not going to rush one minute of this incredible 6 month preparation period here in India — a gift from the Universe — via my Guggenheim and a sabbatical from Stony Brook. PS: For those of you “in the know” about Indian music, I’m learning Bhairov, Yaman, Bhoop, and Marwa, and today we started Lalit. And I learned a little Shree before I came — and incorporated it into one of the Edna St. Vincent Millay songs, Beauty Intolerable, last winter.[Back to top]

January 2013

I contemplated writing an opera based on Khaled Hosseini’s powerful novel for several years. Deciding what you’re going to spend 3-5 — or more — creative years working on is not a small decision for a composer. You have to love the subject and relate to it personally. At least, I do. My first encounter with the novel was in 2009, listening to it as a book-on-tape during my long commutes to Stony Brook. I remember driving down Connecticut’s Route 8, tears streaming down my face as I listened to Mariam’s execution scene, thinking that this was definitely operatic. At that moment I loved and respected Mariam so much. A woman who had suffered unbearable cruelties throughout her life, I wanted to portray her as I saw her…strong, noble, beautiful, having made the ultimate sacrifice of her life — a mother’s sacrifice — for Laila who was like a daughter to her. Upon finishing the novel, however, I was afraid that it was too complex for an opera. Still, memories of it lingered and I bought a copy of the book and read it once more, being more moved on the second reading. In October 2011, I was sitting in the office of Charles Jarden, General Director of American Opera Projects. We were playing with ideas for monodramas — a one person opera — and the execution scene came to mind. But I realized that if the audience does not intimately understand who Mariam is, they can’t appreciate how and why her execution might be transcendent. On the third reading I dared to believe that the novel could work as an opera — ideas for the staged operatic adaptation started coming to mind — and so I gave a copy to my librettist, Stephen Kitsakos, who was as moved by the story as I was. And now, a little over a year after we committed to it, I have met with Khaled Hosseini and obtained the opera rights and his enthusiastic support, and Stephen and I are working on the adaptation. Ideas are flowing in abundance.

If you’ve read this far, chances are you already know the story ofA Thousand Splendid Suns. You also know that the Taliban did (and do) awful things to women and during the late 90’s forced women to wear burkhas, to never go outside unaccompanied by a man, to never show their faces, no music, no laughter, no working outside the home, NO education, NO schooling for women, etc. Much worse was (is) the physical and mental abuse that many women suffered at the hands of their men. In 1997, RAWA, (Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan) was formed under the brave leadership of Meena, to address the suppression of women in Afghanistan. Although Meena was assassinated, her work and legacy continue today. Things are changing. With the international attention A Thousand Splendid Suns received, Khaled Hosseini was able to establish the Khaled Hosseini Foundation which is helping women and children in Afghanistan. The internet abounds with images of the horrors of the mistreatment of women in Afghanistan and indeed even a cover of Time Magazine in 2010, shows the horrors of things done to women in Afghanistan. But, our opera is not about the horrors — it is about how the power of love and hope allows these women to survive. Let’s cut to the heart of the matter. Mariam, an uneducated bastard child of a rich man in Herat, is forced into marriage with Rasheed as a young girl. He abuses her both psychologically and physically after it is clear to him that she will never give him a child. Laila, 20 years younger and stunningly beautiful, is from a different walk of life. Her father was a teacher and she was headed for university studies when the Taliban came to power. She is in love with Tariq, her childhood sweetheart. As the civil war comes to Kabul, he must leave with his family and before he does, they have a moment of unpremeditated love making. He begs her to marry him but out of filial love for her father, whom she can’t abandon, she refuses. She is miserable until her parents decide that they too will leave Kabul. She becomes ecstatic with the hope of finding Tariq, but as they are packing, a bomb explodes destroying their house and killing both of Laila’s parents and injuring her seriously. She ends up being cared for by Rasheed and his wife, Mariam, who live nearby. Mariam knows that Rasheed has always lusted after the young beauty. When Laila secretly realizes that she is pregnant she still has hopes of finding Tariq, but then she is told that Tariq is dead. Rasheed, playing co0l and benevolent, offers to marry her — a woman alone on the streets in Kabul would not survive one day. To protect Tariq’s child growing within her, she quickly accepts his offer and thus begins hell for Laila. At first Mariam and Laila are cool to one another, but eventually they bond. The sacrifice comes several years later when Tariq returns. Rasheed had paid someone to invent a story of Tariq’s death and when he finds out that Tariq has been to the house, he begins beating Laila to death. Mariam saves her life by striking Rasheed with a shovel and killing him. In her two blows are the tears and retribution of unbearable suffering. She insists that Laila escape with Tariq and the children and she will take all of the blame. Laila and the children have given her enormous love and joy. It is right that she be punished for the death of their husband. She accepts her death and feels that Allah will forgive her. She cherishes the fact that although a lowly harami, she was able to experience deep love and was able to sacrifice herself for the survival of her loved ones.

These executions were a regular occurrence with the Taliban. What was this woman’s crime? That she ran away from an abusive husband?

She is a person of consequence. Yes, the emotions are large. That’s why this is such a supreme operatic moment. Stephen and I have a clear vision of the opera. We are excited to collaborate with creative production partners who share our vision and can help us expand it further. American Opera Projects is already on board to help us in the first stages of libretto development. If you would like to learn more about the adaptation, contact me.